While the FAA’s original notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) on Remote Identification drew significant criticisms from the drone industry, the final rules published on December 28th, 2020 have been met with general acceptance. This large shift in public sentiment comes as the FAA addresses its critics and published a more realistic version of its NPRM.

We break down key questions behind the new rules, including what the cost of these rules will be, the significance of the move to broadcast instead of networked identification and how this enables airspace accountability below.

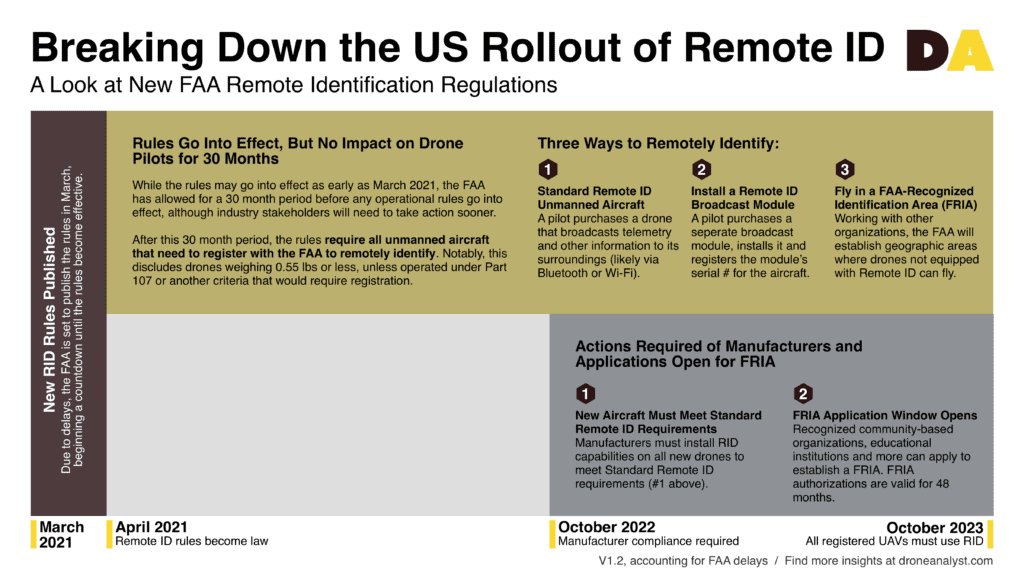

The new FAA Remote ID rules will not be immediately in effect, but instead be rolled out over the next 32 months. We put together a timeline and a general summary in the image below.

What’s the Cost?

The new Remote ID rules minimize costs to consumers and manufacturers by using common, cheap broadcast technologies such as Bluetooth and Wi-Fi. It is even possible that manufacturers repurpose existing Wi-Fi chips in their drones to fulfil this purpose, which could make products today compliant with these new rules at no cost to the manufacturer or customer.

Pilots flying in 2023 that want to operate legacy drones without broadcast capabilities will need to purchase a separate broadcast module and mount it onto the aircraft. While prices for such a module are unclear, they will be cheap. I would estimate broadcast modules will range anywhere from $10 – $40 USD. WiFi modules themselves cost less than $10 (for example, one on AliExpress here), as manufacturers of such modules have reached large scales with the rise of Smart Home products.

DJI has done its own research into the cost of a broadcast solution, as part of DJI’s initial comments about the FAA’s NPRM, and assessed that an integrated broadcast module would cost $2 to the manufacturer (decreasing further at scale) and add-on modules at under $15 at scale.

The FAA estimates the net costs of these rules will be $26.6 million per year. While this number is already small, it estimates that roughly $100 will be spent on compliance per drone, which is likely an overestimation for the above reasons. Manufacturers will need to ensure compliance and will have some upfront costs to do so, but recurring costs to both manufacturers and pilots will likely be far less than $100. A more realistic estimate for annualized costs would be less than $1 million.

Broadcast Beats Networked Identification – What’s the Significance?

The cost and complexity of these new rules are tuned down when compared to the earlier NPRM, with 60% lower annual costs. This is in large part due to the removal of requirements that the aircraft be connected (“networked”) to the internet. This shift in direction does not just mean lower costs to pilots, but also easier compliance and privacy of operations.

The NPRM originally looked to establish requirements that aircraft transmitted their telemetry information to a third-party service provider while in flight. This information would be aggregated and stored online. This posed both a cost hurdle (requiring drones to have SIM cards like phones, likely at a monthly fee) and rose concerns about privacy and the ability to operate in rural areas.

In contrast, the broadcast approach – which the FAA went forward with in these final rules – relies on existing broadcast technologies that are cheap and can be received by your smartphone (and other devices). Similarly, reaching broad compliance will be easier as new drones can easily incorporate (or repurpose an existing) Wi-Fi or Bluetooth module.

Enabling Airspace Accountability

The FAA smartly likens Remote Identification to a “digital license plate” and the new rules do a good job to cement this. The information required to be transmitted by a broadcast module includes the following:

- UA ID (Serial # or Session ID)

- Aircraft flight data

- Position of control station – add-on module uses the takeoff position instead

- Emergency status

- Timestamp

This enables anyone receiving the broadcast to understand what is happening in their surrounding airspace, and where the operator may be located. This DOES NOT allow the receiver to know who is flying the drone. The FAA does not make its registration database connecting operators and the UA ID public. The ability to access or correlate these two datapoint will be restricted to the FAA itself, authorised law enforcement and national security personnel.

Learn More About the Drone Industry

- Explore the new US drone hardware ecosystem and how government policies have supported its growth.

- Learn how DJI’s drone dominance was born, the consumer market faltered and may rise again.

- See how COVID-19 has increased interest in consumer drones.

- Understand the four forces that shaped the drone industry in 2020.

Thanks David for the basic opinions on the new rules. But, I do have a question regarding the new rules regarding flying over people. From what I’ve read, drone operators will need to adhere to an impact energy of 11 ft-lbs or 25 ft-lbs, depending on which class they fly under. These are pretty low numbers given that a 2 pound drone falling 400 feet is going to have considerably more energy. How is this going to be accomplished? The only thing I can see that will reduce the energy that much will be parachutes, which some people already use. They’re expensive too. What’s your take on this? Thanks!!

Hey Rick, great question. I’m still diving into the ops over people regs, which are much more nuanced. I should have something together next week. I’d be a bit worried if the widespread answer to ops over people are parachutes, due to expense and also complexity.